We have updated the content of our program. To access the current Software Engineering curriculum visit curriculum.turing.edu.

Async JavaScript with Promises

Learning Goals

- Understand the difference between synchronous and asynchronous JavaScript

- Understand the ‘Event Loop’, and how it relates to asynchronous JavaScript

- Be able to implement a network request using the

fetchAPI - Know when and how to use Promises and why they’re useful

- Understand the relationship between Promises and callbacks

- Understand modern ways of writing asynchronous JavaScript through

async&await

Vocab

AsynchronousExecuting functions, where the second does not wait for the first to completeSynchronousExecuting functions, where the second waits for the first to complete- Event Loop

ParallelismExecuting more than one operation at a timePromiseAn object representing the eventual completion or error of an operation, along with a valueCallbackA function given to another function to be called at a later timeHigher Order FunctionA function that either takes a another function as a parameter or returns a function, or both

Synchronous vs. Asynchronous JavaScript

Before we get into dissecting Promises, we need to make sure we understand the difference between synchronous and asynchronous JavaScript. In client-side JavaScript, most of the code we write will be synchronous. This means that our code is read and executed line-by-line, in the order that it’s written:

thisFunctionWillExecuteFirst();

thisFunctionWillExecuteSecond();

thisFunctionWillExecuteThird();

imGoingToTakeForever();

iCantExecuteUntilSlowPokeAboveMeIsDone();

Asynchronous JavaScript, on the other hand, will be processed in the background – it will not block the execution of the code that follows it. This comes in handy when we want to pull a slow or expensive operation out of the default synchronous flow of execution. The newest, hippest way to do this is by using Promises.

An Aside - The Event Loop

In order to understand the difference between the two, we should take a closer look at the JavaScript runtime (aka the Event Loop).

The JavaScript runtime is made up of:

- A

Heapwhich holds variables and the like - A

Stackwhich is single-threaded in JS. It holds a list of the currently executing functions and their arguments and local variables (frames). TheStackis Last In First Out (LIFO) - A

Queuewhich holds a list of functions (messages, actually, that point to functions). TheQueueis First In First Out (FIFO) - An

Event Loopwhich watches theQueueand theStack, and takes the first function from theQueueand puts it on theStackwhen theStackis empty.

Executing programs by adding and removing stack frames is synchronous.

Adding events to the Queue so that functions may be executed later is asynchronous.

Turn And Talk

Take a moment and draw out a diagram in your notebook. Then discuss with your partner what are the different parts of the Event Loop? Which parts are synchronous and asynchronous?

Feel free to watch this talk later to help in your understanding.

Enter the Promise Object

Promises allow us to kick off an asynchronous process in the background and respond to its result when it becomes available. Let’s start off with how we can create a promise.

The syntax can look squirrelly at first, but if we pull it apart, it’s not that bad. If you open up the console in your browser dev tools, you can actually create your own Promise object and inspect its inner workings:

let foo = new Promise();

Done. Well, not quite. We also need to give it the mechanics for how it should handle fulfillment or rejection. So, we hand the Promise constructor a function that will dictate how we figure this all out.

let foo = new Promise(() => {});

Okay, here’s where it gets a bit hectic, that function is going to be handed two arguments, which are both functions as well.

let foo = new Promise((resolve, reject) => {});

As you can probably imagine when things go well, you should call the resolve() function. If things blow up, then you should use the reject() function.

let foo = new Promise((resolve, reject) => {

if (true) {

resolve('Here is the data you retrieved!');

} else {

reject('There was an error retrieving your data');

}

});

Logging what foo looks like you can see that it resolved and gives us a value. If we want to see what it looks like when it rejects, we can change the conditional so it looks like:

let bar = new Promise((resolve, reject) => {

if (false) {

resolve('Here is the data you retrieved!');

} else {

reject('There was an error retrieving your data');

}

});

An error will occur giving us the message when reject is called. Logging what bar looks like will give us a Promise object with the rejection value.

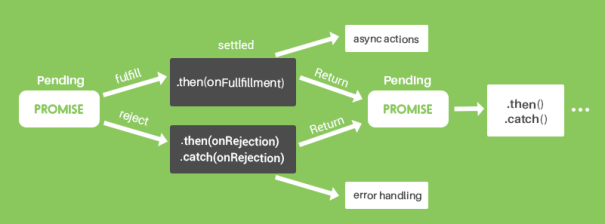

Unless you’re making a library or creating an abstraction over something complicated, you’re likely to consume promises more than you create them. The promise object itself encapsulates all of the asynchronous logic and allows whoever receives this promise to just deal with it using .then() and .catch() methods as we will see in examples below.

The Promise-Based Fetch API

The most common example of an async process we’ll run into on the client-side is a network request. Making a trip to the server can take a significant amount of time, and our applications would be painfully slow if they stopped the rest of our code from executing. Combining this knowledge with what we’ve just learned about Promises, it’s reasonable to assume that there would be a web API that facilitates making promise-based network requests. The fetch API allows us to do just that. A typical fetch request might look like this:

In this example, we are making a GET request in order to get a random joke. Every fetch request we make will return a Promise object that contains our response data. This allows us to easily react to the type of response we get once it’s available. By returning a Promise object, this function does two very important things:

- It automatically becomes asynchronous, allowing it to run in the background and giving the rest of our code a chance to continue execution.

- It gives us access to two methods:

.then()and.catch().

If the fetch is successful, the Promise object is considered resolved, and our .then() block will execute. While we wait for the server to return our response, the rest of our application can continue executing other code in the meantime. The response object returns a lot of extra information that we don’t necessarily need. All we want in this scenario is a JSON object of our project data which we can get by calling response.json().

Converting the body to a JSON data structure with response.json() actually returns another promise. (Converting the data to a particular type can take significant time, which is why we have this additional promise step before we can begin working with our data.) Because we’re getting another promise object back, we can simply chain an additional .then() block where we actually receive our project data. In the final callback, we will receive the data in an object (in this scenario, a joke). We can then render this on the DOM.

If the function fails for any reason, our Promise object is considered rejected, and our .catch() block will execute instead. Within this block, we are automatically given an error that we can use to notify the user that something went wrong.

Passing the Options Argument

The syntax would look fairly similar if we wanted to make a POST or DELETE request. One thing to note is that fetch can actually take two arguments:

- the URL or API endpoint we’re trying to hit

- an optional object of configuration settings for our request. This object may contain what kind of request we’re making (e.g.

GET,POST, orDELETE) and any data we might need to pass along with it

const options = {

method: 'POST',

body: JSON.stringify({

jokeName: 'Another bad joke',

jokeValue: 'What did the triangle say to the circle? You’re so pointless.'

}),

headers: {

'Content-Type': 'application/json'

}

};

fetch('/api/v1/jokes', options);

In this example, we’re making a POST request that would add a new joke. We would handle this promise with both a .then() and .catch() just like our example above.

const options = {

method: 'POST',

body: JSON.stringify({

jokeName: 'Another bad joke',

jokeValue: 'What did the triangle say to the circle? You’re so pointless.'

}),

headers: {

'Content-Type': 'application/json'

}

};

fetch('/api/v1/jokes', options)

.then(response => response.json())

.then(joke => renderJoke(joke))

.catch(error => console.log(error));

Why Use Promises?

Promises allow you to multi-task a bit in JavaScript. They provide a cleaner and more standardized method of dealing with tasks that need to happen in sequence. (For example, we couldn’t have possibly called renderJoke() until we actually received the joke data from fetchRandomJoke()). With Promises, we have more control over what happens with the outcomes of our async processes.

An Alternative to Callbacks

As we mentioned before, a Promise is essentially an IOU that says “Ok, I’m going to get you the information you requested, just give me a second. In the meantime, go do whatever else you need to do, and I’ll let you know when I’m ready.” This is almost similar to event listeners that you may have written in the past. Take a click handler for example:

$('button').click(() => {

doSomething();

});

When this code first executes, it doesn’t actually fire doSomething(). It simply binds the handler to our button element. Recognize how it takes the execution of doSomething() out of the natural synchronous flow and holds onto it for later – to execute only after a click event has occurred. This is a common convention in client-side JavaScript and is called the callback pattern.

The callback pattern, in short, is when you pass a function as an argument to another function to be executed later. This pattern has historically been wildly popular because it’s easy to implement. But it has a few problems:

- Doing things like executing callbacks in parallel and waiting for all of them to come back is tricky.

- Doing things in series where one callback hands its data to the next callback is also tricky. (This has the delightful nickname of “callback hell.”)

- Error handling is inherently broken. There are a number of clever ways to get around this:

- Pass two callbacks—one for a successful outcome and one for an unsuccessful outcome.

- Use the Node.js “error-first” style of callbacks where the first argument is always an error object, which is typically set to

nullin the event that we reached a successful outcome. This is incredibly pessimistic.

Let’s take a look at some more intricate examples of the callback pattern. Using jQuery’s getJSON method, (which can be written with callbacks or promises), we could make a network request that takes three arguments. The first is the endpoint we want to hit, the second is our success callback and the third is our error callback:

// Using callbacks

$.getJSON('/api/v1/students.json', (students) => {

console.log(students);

}, (error) => {

console.error(error);

});

When re-written as a promise,we can leverage methods like .then() and .catch():

// Using promises

$.getJSON('/api/v1/students.json')

.then(students => renderStudents(students))

.catch((error) => console.log(error));

While not looking incredibly different, the callback pattern begins to fall apart when we need to do multiple operations in sequence:

// get the student data

$.getJSON('/api/v1/students.json', (students) => {

// get the projects for all students

getProjectsForStudents(students, (projects) => {

// get the grades for each project

getGradesForProjects(projects, (grades) => {

// finally, render all of our student/project/grade data

renderAllData(students, projects, grades);

// handle errors getting student data

}, (error) => {

console.error(error);

})

// handle errors getting project data

}, (error) => {

console.error(error);

})

// handle errors getting grade data

}, (error) => {

console.error(error);

});

Or in other words…

Ugh. This is what we refer to as callback hell. The code becomes super nested and difficult to follow. Without comments, it’s not clear which error callbacks are associated with which operation, and there is a lot of repeat code. When re-written using promises, we can consolidate and flatten a lot of this syntax:

$.getJSON('/api/students.json')

.then(students => getProjectsForStudents(students))

.then(projects => getGradesForProjects(projects))

.then(grades => doSomethingImportantWithAllThisData(grades))

.catch(error => console.log(error)));

This reads a lot better than that callback example, right? If you came back to this code in a few weeks or months, you’d probably still be able to grok the general idea of what it does.

Note 1

Going forward, it is best to use the fetch API for making network requests. Using getJSON in this lesson is purely to demonstrate the difference between a callback implementation and promise implementation. fetch can only be used with Promises and is steadily becoming the industry standard.

Note 2

When you read the documentation for a library that uses promises, one of the first sentences will likely say ‘this is a promise-based library’. There are some APIs that still use callbacks rather than promises (the geolocation API, for example). You’ll want to read the documentation closely to see if the library expects you to use a promise or callback. So for once, we don’t really have to be in charge of making a decision here – we can let the tools and technologies we’re using dictate whether or not we should be using promises.

Advantages of Promises

So besides the obvious syntactical benefits, what are some of the others advantages of promises?

- You are getting an IOU that you’re holding on to rather than giving your code away as you would with callbacks.

- Error handling is less broken. It’s not a silver bullet. Synchronous functions either

returnor throw an error. In a similar vein, your promises will either become resolved by a value or become rejected with an error. - You can catch errors along the way and deal with them in a way that is similar to synchronous code.

- Chaining promises is easy and does not result in callback hell.

But wait, there’s more.

Promise.alltakes an array of promises and waits until all of the promises are resolved. This solves the nastiness involved in doing this with callbacks.Promise.racetakes an array of promises and resolves as soon as any one of them fulfill. This would allow you to hit 3 API endpoints and then move on when we heard back from whichever one came back first.