We have updated the content of our program. To access the current Software Engineering curriculum visit curriculum.turing.edu.

Taming Merge Conflicts

Git Workflow

So far, your git workflow has probably been something like this:

- create a feature branch based off of master

git checkout -b feature-branch - make some commits to your feature branch

- open a pull request to merge your feature branch into master

- resolve any merge conflicts that are detected in the pull request

- merge the pull request into master

This works fine, but there are a couple of downsides here:

- If you open a pull request that contains merge conflicts, whoever is reviewing your code is likely going to tell you to resolve your merge conflicts before they review. This can slow down the review process. We’d like to open our pull requests in the best state possible, which means resolving any merge conflicts beforehand.

- When you resolve your merge conflicts through the GitHub UI, it automatically generates what’s called a “merge commit”. While merge commits can sometimes be helpful, in this scenario, it mostly just clutters up our history and makes it more difficult to understand the evolution of our project.

Workflow Goals

In order to avoid these two pitfalls, we have some workflow goals:

- resolve any merge conflicts in our text editor before opening a PR by periodically pulling changes from master into our feature branch

- avoid creating “merge commits” by using a rebasing workflow

Merge Commits

Let’s talk about merge commits first. Merge commits are auto-generated commits that detail how and when one branch was incorporated into another.

Sometimes, merge commits can be helpful. When we merge a pull request into master, a merge commit will help us identify what changes were made in that pull request, who made them, and who approved them. We care about what gets merged into master, because master is our default branch and we want to keep track of how any changes make it in. See below:

Other times, merge commits are less helpful. When we resolve merge conflicts in the GitHub UI, behind the scenes it’s saying “merge the master branch into this feature branch”. These commits are less helpful because we don’t really care how changes get incorporated into our feature branches. We’re not deploying these branches, they’re going to get deleted eventually anyway – they’re short-lived. We don’t need to know how and when you resolved your merge conflicts.

Take a look at this merge commit that resulted from resolving merge conflicts:

- There are 3 completely unrelated changes in this commit

- It looks as if only Brittany made these changes, when in reality it was multiple people

- I lose any of the original commit messages made with these changes and instead just get a general “merge gh-pages into this branch” commit message that doesn’t help me understand the changes involved

So What?

It may not seem like a big deal to have all of these merge commits in your history – you likely haven’t yet had to dig back into your history much. But when codebase changes are happening very fast, there are a lot of people contributing code, and it’s important that the app is always up and running without bugs, being able to search your history and revert to an earlier version is going to be crucial. Merge commits make it much more difficult to do this.

Merging vs. Rebasing

So far we’ve been introduced to the merging workflow for git, which allows us to integrate changes from one branch into another. While this works just fine, there are some disadvantages that have made it more popular to adopt a different type of workflow: rebasing.

Rebasing serves the same purpose, integrating changes from one branch into another, but it does so in a more streamlined fashion. You will more commonly see teams using the rebase workflow, so it’s important to be familiar with it when collaborating on open source projects or joining new teams.

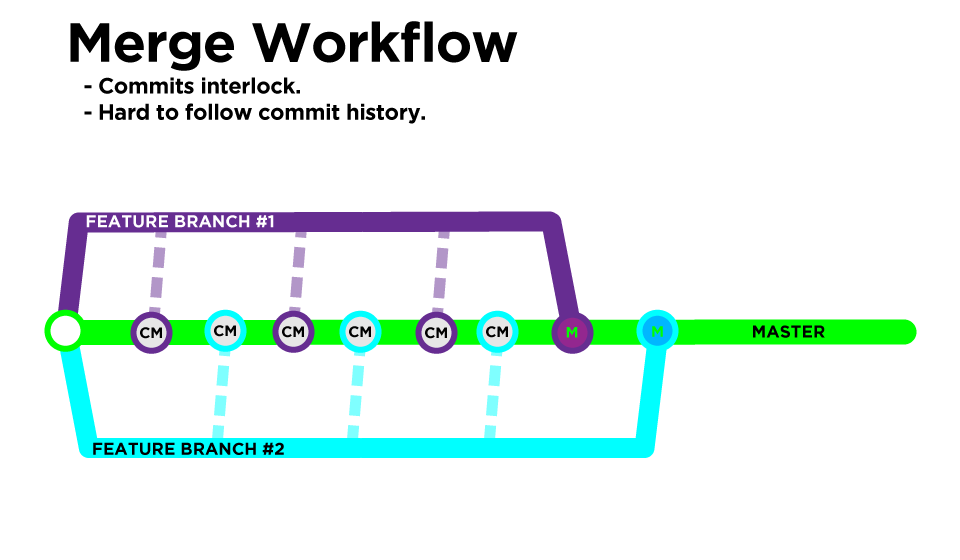

Merge Workflow

repo-name:feature-branch $ git merge master

What you’ve been doing so far is considered the merge workflow:

- commits interlock based on when they were made

- merge commits are generated any time we have to resolve conflicts

- makes it more difficult to read the history

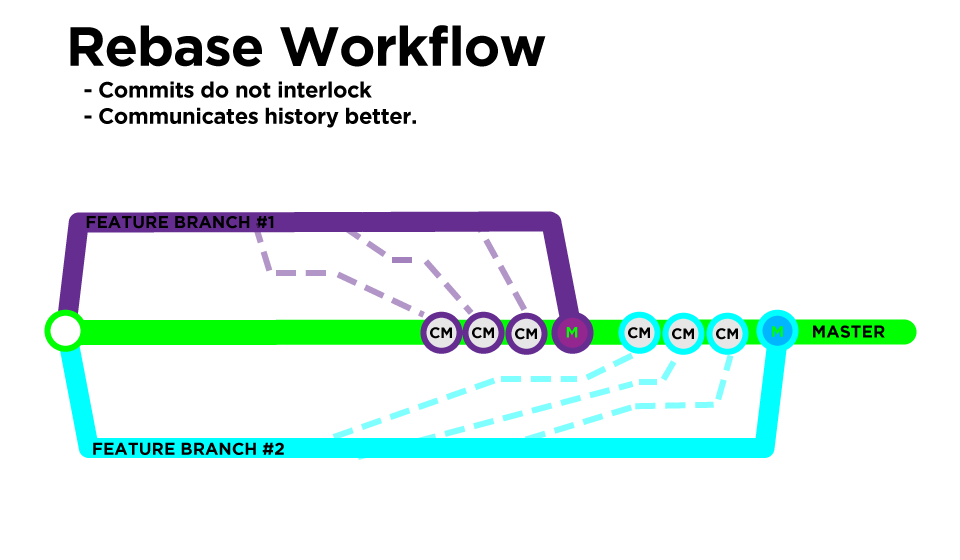

Rebase Workflow

repo-name:feature-branch $ git pull --rebase origin master

Another workflow option is called rebasing:

- feature branch commits are applied on top of any other commits

- conflicts are resolved during the rebasing process and do not result in merge commits (you should be rebasing almost as frequently as you’re committing)

- makes it easier to read the history

So rebasing helps us accomplish our two goals we set for ourselves at the beginning of the lesson, but there are some downsides:

Because you’ll be resolving merge conflicts in each commit, and because you’ll be moving your commits to the tip of the branch (despite their timestamps), you’ll essentially be changing the work that was done in that commit. This is called rewriting history, and it means that your commit will get a brand new SHA identifier.

This is important, and where rebasing gets tricky. Any time you rewrite history there is potential for collaboration to get thrown off track. If anyone has based any work off of your commits with their original SHAs, and then you rewrite history, git won’t be able to successfully combine those changes any more.

To avoid any issues with rewriting history, we must follow the golden rule of rebasing:

Only rebase on branches that you are working on alone. As soon as you push up that branch for someone else to review or contribute to, stop rebasing