We have updated the content of our program. To access the current Software Engineering curriculum visit curriculum.turing.edu.

All the databases

Learning goals

- Understand the types problems that the different databases solve

- Understand the basic syntax structure for querying each database

- Can read and write records in the database

- Can start a new project in each database

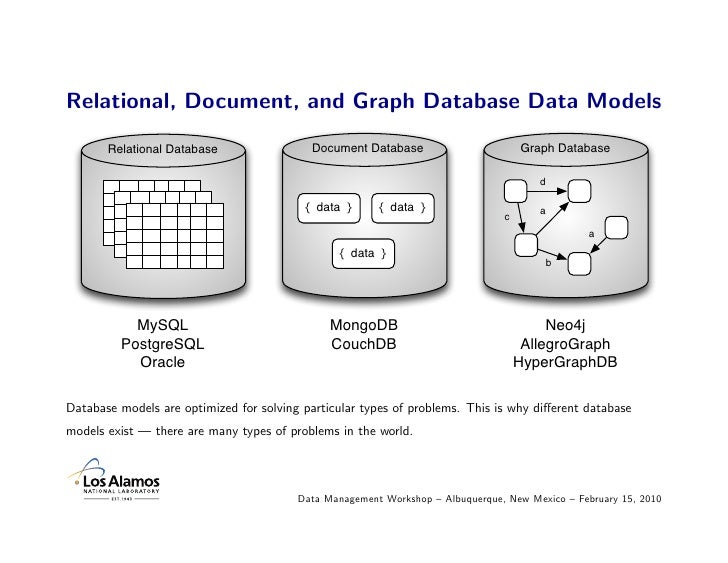

Relational databases

Engines

A database engine is like an implementation. The thing that actually stores and manages your data on a hard drive. Here are some example relational engines:

Uses

Many. Most. Like 80% of the time, you want a relational database. If you aren’t sure if any other database type will work, this one probably will.

Pros

- Lots of people know it. Lots of libraries and ORMs

- Fast queries of complex databases

Cons

- Slow to change. Schema has to be well planned

- Traditional engines don’t scale well. You have to consider using something else once you get to 100M-1Bn records

Overview (and some vocabulary)

Table

Many tables will exist in each relational database. Easiest to think of this as a spreadsheet. Each row is a “record”.

Column

Continuing our spreadsheet metaphor, each table has a number of columns. Each record in the database has the same columns. Columns are also called fields.

Id

A special column that identifies a specific record in a table. It’s special because it’s unique (no two records have the same value) and it’s indexed (the database knows exactly where the data is stored by it’s id). Ids are not required, but they’re kind of the point of relational databases.

Foreign Keys

Now we get to the relational part. Some tables will include special columns that refer to id columns in other tables. We refer to these columns as “foreign keys”. Foreign keys are the basis for all record relationships in a relational database.

Schema

Some representation, usually visual, of the tables, columns, ids and foreign keys that make up a database. Basically, all the structure without the data.

SQL

Structured Query Language is it’s own language. It has variables and functions and every database engine has it’s own dialect. It’s used mostly for reading and writing data, but it can do logic and calculations on your data, often much more quickly than your silly ruby or JavaScript can.

Insert

For creating new records in a given table. A generic and a specific example:

INSERT INTO table_name ( column_1, column_2 ) VALUES ( value_1, value_2 );

INSERT INTO users ( name, email ) VALUES ( 'Nate Allen', 'nate@turing.edu' );

Select

For getting some set of records from a given table. Some examples:

SELECT column_1, column_2 FROM table_name WHERE conditional AND another_conditional;

SELECT * FROM users WHERE name='Nate Allen';

Select statements are very powerful, and let you slice your data however you desire. You need only take the time to learn the syntax.

Join

Join is where the magic happens. This is how we combine data from multiple tables through those foreign key relationships.

Joins are part of select queries. Since SQL doesn’t care about whitespace, here’s a multi line select query using a join:

SELECT posts.title, posts.description, users.name as author

FROM users

JOIN posts ON users.id = posts.user_id

WHERE user.id = 1;

This will return us the title, description and author of each post for the user with an id of 1.

Reference material

- Good intro to a whole lot of SQL functionality

- SQLite command line reference

- Postgres command line cheat sheet

Exercises

- Here’s a sandbox: http://www.dofactory.com/sql/sandbox

- List the first and last name of all the customers

- List all fields for customers from Germany

- Insert a new customer record for yourself. What’s your id?

- List all the orders from Maria Anders (hint: you don’t need a join yet)

- Return the sum total amount from all of Maria Anders’ orders

- Return the number of customers from each country

- Some Backend Mod 2 lessons:

- http://backend.turing.edu/module2/lessons/visualising_and_implementing_database_relationships

- https://github.com/turingschool/lesson_plans/blob/master/ruby_02-web_applications_with_ruby/outlines/introduction_to_sql.markdown

- A Backend Mod 3 lesson: https://github.com/turingschool/lesson_plans/blob/master/ruby_03-professional_rails_applications/intermediate_sql.md

- A nifty sandbox. Try these things:

- List the first and last name of all the customers

- List all fields for customers from Germany

- Insert a new customer record for yourself. What’s your id?

- List all the orders from Maria Anders (hint: you don’t need a join yet)

- Return the sum total amount from all of Maria Anders’ orders

- Return the number of customers from each country

- Return the concatenated first and last name of all customers

- Creating a hybrid document/relational database: http://rob.conery.io/2015/03/01/document-storage-gymnastics-in-postgres/

SQL in code

ORMs

ORMs are beyond this spike, but if you’re curious

Document Store

Engines

Overview

Collections

Collections are really just groups of documents. You usually put documents that represent the same kind of resource in a collection.

Documents (Basically JSON)

Most of the time, a document is just a set of key/value pairs. Think of a document as some JSON. In some engines, documents are XML.

Key/value pairs

A value is the actual data being stored. A key is some string used to access that data. It gets complicated when your value is a key/value pair itself, thus nesting sets of data.

Arrays

It felt worth mentioning that a value can also be an array. The root of a document can also be an array.

Map/Reduce

Map and Reduce are commonly used together when querying a document store DB. You might be able to guess what they mean from other programming. Mapping is taking a set of documents, and normalizing their data into a consistent structure. Reducing is taking that set of data and running calculations on it. “MapReduce” is also the name of a database from Apache

The Hype

- Storing data is stupid simple. Minimal planning necessary

- Reading, writing, mapping and reducing scales really well across multiple machines for huge data sets. Distributed relational databases exist, but they’re expensive and specialized, or slow.

Anti-hype

- The queries are the hard part

- Schemas are not as straight forward. There’s some amount of trial and error when doing queries, and queries can break if a document gets added that doesn’t conform.

No(t)SQL

A decent cheat sheet for common things

Insert

db.collectionName.insert({some: {javascript: object}})

db.users.insert({name: "Nate Allen", email: "nate@turing.edu"})

Find

db.collectionName.find({someKey: someValue})

db.users.find({name: "Nate Allen"})

Getting Started

brew install mongodb

Then follow the instructions to start a server

For a really simple GUI, try robomongo

Exercises

I wrote a JavaScript to fill a collection with TV shows and episodes. To give you something to play with. Here’s a gist of it

There’s also a sample dataset from the mongo people

- TV Shows

- What is the rating of Westworld?

- How many shows were not shown on TV?

- How many shows have less than 20 episodes

- How many shows have only 1 season?

- Create an episodes collection. Move all of the episodes into this collection with a reference to the show.

- A kind of wordy tutorial. Good for a deep dive.

- Getting started if you need it: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dawwpoMrOtw

- Build a site with Node/Express/Mongo: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Do_Hsb_Hs3c

In code

Graph Databases

Engines

- Neo4j

- Lots of others (not sure which ones you’ll encounter)

Overview

Nodes

A.K.A Quads. A.K.A. Vertices. These are the resources. Each node can be it’s own class, but typically you have several nodes of the same class.

Edges

A.K.A Triples. A.K.A. Relationships. These describe the relationship between nodes. They connect in one direction, and describe the relationship of one node to another. They are not reciprocal, meaning you often have two relationships in opposite directions between the same two nodes.

Properties

Nodes and Edges have properties. There is no requirement that properties are consistent. They can be whatever you want on each new thing you create in the database, although consistent properties are going to make your queries easier.

What does this all look like?

An example of relational databases breaking down

Getting started

You need to install the JDK before you can install Neo4j. Type javac -version to see if you have it. If you don’t you’ll probably be prompted to install it. You can try that. I haven’t. If you’re already a user of brew cask, just brew cask install java. Otherwise, download from here

Then you can brew install neo4j and follow the instructions to start the server.

If you want to skip the java installation entirely, and I wouldn’t blame you, you can also sign up for an online sandbox here: https://neo4j.com/sandbox/

Exercises

Neo4j has a really nice set of tutorials after you get up and running. I’d also play with this Game of Thrones dataset